Relative knowledge

As a research scientist, (one my) tasks(s) is to perform

“creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge".

according to the definition of research by the OECD. To increase knowledge we need to know what we know, so we can study effectively and know what others know, so we can communicate effectively. These things are not that simple.

Knowing what another person knows

An important part of research is discussing your ideas with peers. Efficiently conveying a message means knowing what the other end already knows. If you start from scratch you waste the other person’s time. If you dive in too deep immediately, the person at the other end will have no idea what you are talking about. This concept is somewhat related to a concept from cognitive psychology known as a ‘theory of mind’ in psychology and refers to the ability to accurately develop models of other people's mental state.

Knowing exactly what someone knows and where this person is is very difficult though. Progress often comes with the realization that complex ideas you once had are worthless. Sometimes you may feel like you are far ahead of someone who does not see a trivial solution. The other person may think of you as dumb, because you do not respond to their complex ideas. It is difficult to know who is really right.

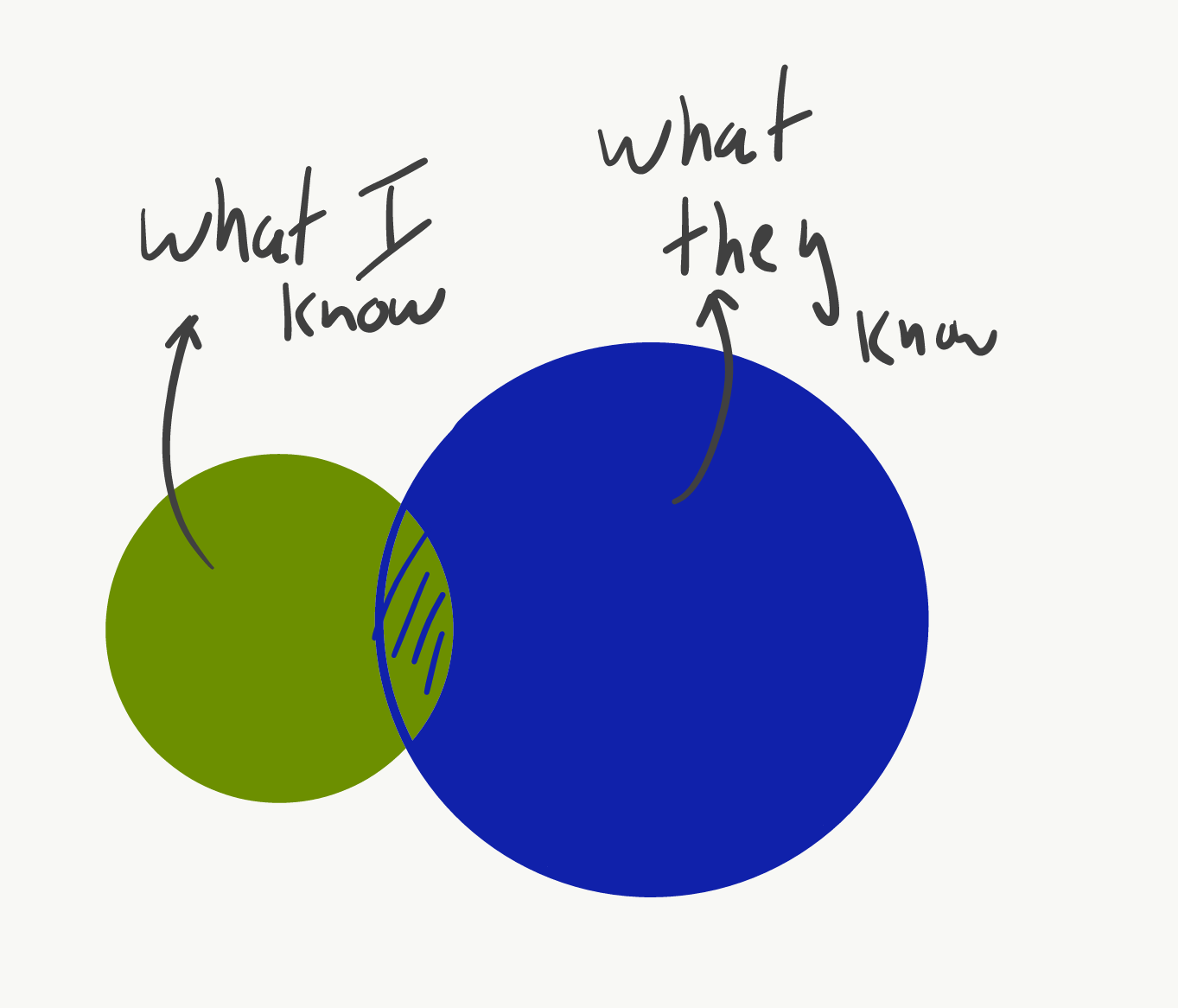

Estimating someone else’s knowledge is particularly important in job interviews. Although many skills are probably (more) important than raw knowledge (general intelligence, problem solving capabilities, ability to reason, rigor, grit, etc), lets summarize all that into the term ‘knowledge’. Consider these two scenarios, depicted below. In the first case it seems like the other person may not know so much/may not be so capable, because the overlap is quite small, though the person is actually far more knowledgeable. In the second case, it is the other way around. How do you know where you stand and who have you rejected/when have you been rejected based on a wrong assessment?

Knowing what there is to know

Related to the first point is knowing where you stand yourself, not only with respect to one particular person, but with respect to everyone else. This is also very tricky and it turns out people often overestimate their abilities when new to a certain task or field. This phenomenon is called the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias first described by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger.

The Dunning-Kruger effect relates the ‘true’ competence and self-perceived competence. It turns out there is a u-shaped relationship between actual competence and perceived competence. Novices are often overconfident in their abilities, not knowing enough that they don’t know anything and can not see their own mistakes and shortcomings, intermediates know enough to know that they don’t know anything and tend to be less confident than a less skilled or knowledgeable person, experts are confident in their abilities, yet overestimate the knowledge of others. This can result in debates where an intermediate is overruled by a novice because of their relative perceived competence.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is perhaps one of the reasons why Elisabeth Holmes decided to revolutionize blood tests as a first year Stanford drop out and why everyone in the world confidently argues about COVID19 policies, results and treatments that are set out by experts with 40 years of experience in virology or epidemiology.

See also:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pOLmD_WVY-E

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y50i1bI2uN4